Like the Great Pyramids, the Great Sphinx, the Parthenon, Venice, Florence, and Pisa, Pompeii was one of the Big Deals for me on this trip. It was exciting just to drive past Mt. Vesuvius on our way to Pompeii. This is the only volcano on Europe’s mainland that has erupted within the last 100 years. It is considered to be one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world because 3,000,000 people live close enough to be affected by it; 600,000 people live in the “danger zone,” making it the most populated volcanic region in the world.

Pompeii was the Beverly Hills or the Monte Carlo of the first century. Extremely wealthy people made Pompeii their playground for gambling, games in the forum, the theater, the baths, and—let’s say “the pleasures of the flesh.” These wealthy people had 180 days off every year and didn’t work after 11:00 a.m. during the rest of the year. It was truly a city of pleasure where slaves did all the work.

Educated and skilled slaves were very valuable and could cost $2 million in today’s money. These slaves might have been Greeks who could teach Latin, mathematics, philosophy, etc. or skilled blacksmiths, carpenters, tailors, and the like. Because they were so expensive, they were well cared for—an investment to be protected. Some people who were educated or skilled volunteered to become slaves because, after a certain number of years, they were given their freedom as well as enough money to begin their own careers.

Our bus dropped us off on the street and, without a traffic light, we crossed a multi-lane busy street to this wide sidewalk. Our guide told us there are hand signals between drivers and pedestrians. (Of course there are hand signals—this is Italy, the country famous for hand gestures while speaking.) The driver might briefly put a hand over his eyes to say “I don’t see you, so I’m not stopping.” In response, a pedestrian might point a finger at his/her chest, then two fingers at his/her eyes, and then a finger at the driver to say, “I see you and I know you see me, so I’m crossing the street here.” Our guide added that the only way to get across a street here was to “cross with confidence,” so we did, and it worked. When we confidently stepped into the street, the traffic stopped for us. I like the decorative sidewalk. It’s a very wide sidewalk because it leads to the entrance to Pompeii, and lots of tourists visit the site.

The first thing we saw when we entered Pompeii was the Quadriportico of the Theater where people could mingle before the performance started. The upper seats of the Theater can be seen in the center background. After the 79 AD eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, the ashes covering this quadrangle were 19-23 feet deep.

This was the main street of Pompeii. Look at all those tourists!

The streets of Pompeii slanted downward from the center to drain the water into the aqueducts. This also removed waste from the streets. The large rocks crossing the street are stepping stones so that pedestrians could avoid stepping in puddles when they crossed the street after a rain. The stepping stones were strategically placed to allow cartwheels to pass between them, and so many carts used the streets that “cart tracks” are worn into the stones. To this day, the distance between those cart wheels is the standard for trains in Europe.

Here’s Ted, trying out the stepping stones and keeping his shoes dry. (There were morning rain showers in this area.)

The Romans were so clever that, before street lighting, they placed small white pebbles among the rocks on the roads. The white rocks reflected light at night and helped people stay on the road after drinking and gambling into the wee hours.

Pompeii was a Roman colony in the first century, so it had an aqueduct system that supplied water, removed waste, and filled fountains and baths. This is one of 40 drinking fountains in Pompeii that has been restored and delivers free water through pipelines from nearby towers. Drinking fountains like this would have been on a commercial street.

This was the commercial district that included the fountain in the photo above. It looks like the big box store area. Do you think they had a first century Target?

Shops can be identified in the ruins because they had slots in the doorway stones where sliding doors operated. The sign says “Domus Cornelia” (House of the Cornelii). This was one of the buildings that had a fountain in its atrium.

This was a residential street in the city.

Pillars like this one on street corners identified streets and buildings on those streets. This pillar has an icon showing two men carrying what is probably a container of olive oil on a pole, indicating that delivery persons lived on this street. The sign also provides the information “REG-VII-INS-IV” which indicates that it is Region 7 (REG for “regio,” a section of the city), and apartment/house (INS for “insula”) number 4 (IV). So it means Region 7, Apt. 4 on the delivery workers’ street. Postmen or visitors could find the appropriate sign, then shout down the street for the person they wanted to see (no doorbells or knockers).

The theater provided popular entertainment. This large theater was for wealthy people, and originally seated about 5,000 spectators. Powerful, rich men sat in the lower front seats; less powerful and less rich men sat in the middle rows; women and children sat in the uppermost rows. (I’ll keep my feminist thoughts to myself here.) Greek theater focused on tragedies, but the Romans liked entertainment (especially in Sin City/Pompeii), so their plays included gladiators, ferocious animals, executions, etc. (Executions are entertainment??)

Amazing special effects were possible on the theater stage. A devil could come up from the Underworld in a burst of flame or a god could appear to help someone in distress.

The lower classes of the city had a smaller theater with a seating capacity of only about 1,000 spectators.

There were very few private baths in the first century. The public baths in Pompeii played an important social role as a place where people could work out, relax, and meet other people. They could also get clean, which they did by putting oil on their skin and then scraping it off before rinsing with water. The Stabian baths in Pompeii are the oldest bath complex in the city, and they’re right near the brothel. Handy. They’re called Stabian baths because they were located at the corner of the Via Stabiana. Well, duh!

Because the Romans were so advanced with water systems, these first century baths had running water connected to the aqueduct system, and they included a swimming pool in addition to hot, tepid, and cold baths and a sauna. They were heated by piping systems circulating hot air from furnaces into the walls and doubled floors. The baths also included changing rooms, latrines, and a gym. Men and women had separate quarters, but the men’s quarters were far more lavish than the women’s. (Feminist thoughts again unstated here.)

Here is the entrance to the baths at Pompeii.

The sauna was heated with water beneath the floor to create steam. You can see the double floor where the water was contained to heat the bath. Because the sauna was so hot, it was opposite the cold bath, shown in the second photo. The cold bath was supplied with cold water through the hole near the floor.

All the baths, including this tepid bath, were originally beautifully decorated.

When Mt. Vesuvius violently erupted in 79 AD, the ash cloud rose 21 miles upward. The first blast was heat. It was so hot that the contorted bodies were not evidence of agony; they experienced a cadaveric spasm in which their organs and blood were vaporized. At least one victim’s brain was vitrified (turned to glass) by the temperature of the blast. If a person survived the heat blast, they were quickly suffocated by the ashes or burned by the hot rock and gases that flowed at speeds up to 150 mph. The volcano erupted for three days. Anyone who survived until the third day later suffocated from the small lava pebbles that fell in enormous quantities. It is estimated that 2,000 people were killed by this volcanic eruption.

Contrary to popular belief, intact bodies were not found by excavators in Pompeii. During the excavation process, voids were discovered where humans and animals had perished. Plaster of paris was injected into the voids and took the shape of whatever had perished in that spot. More than 200 plaster casts were made during the excavation of Pompeii.

This is a cast of a pregnant female slave. She is identified as a slave because she is wearing a belt at her hips. It’s known that she was alive after the heat blast on the first day because she had time to roll over and cover her face in an attempt to survive before she suffocated from the lava pebbles that fell relentlessly later in the eruption.

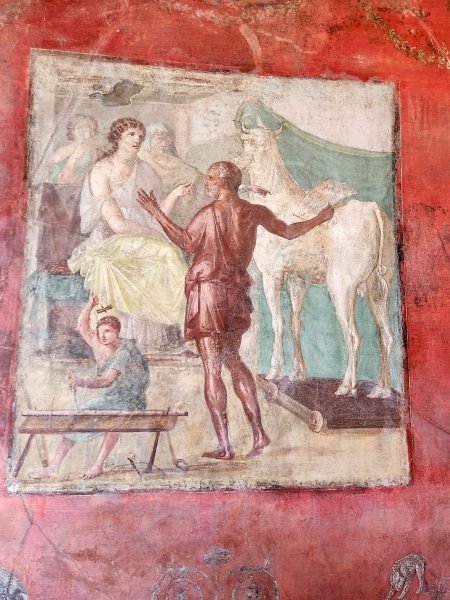

The Vettii family were the richest and most famous people in Pompeii, and their house—the House of Vettii—was one of the grandest houses in the city. Pompeii was known for its explicit and erotic artifacts and the Vettii house is filled with erotic paintings and friezes. The concept of obscenity seems to have been unknown in Pompeii because love and sex were encouraged without prejudice for homosexuality or prostitution.

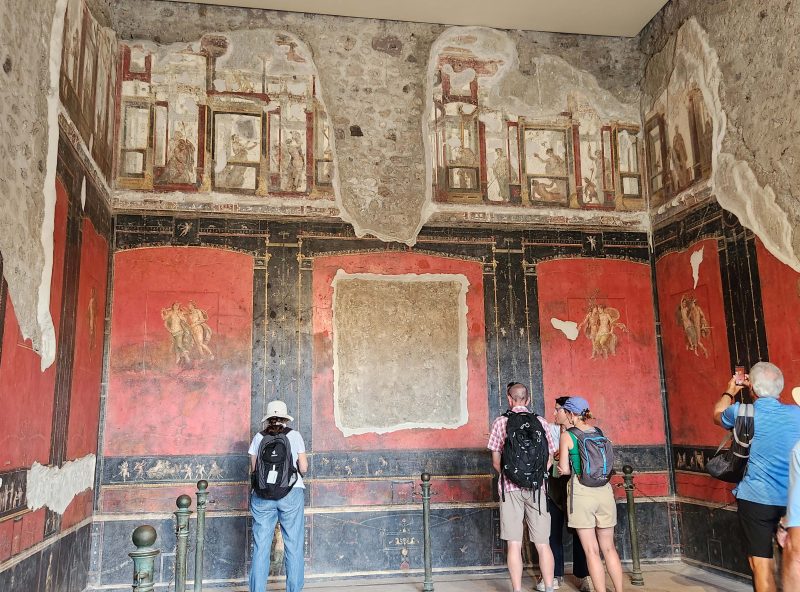

The dining room of the House of Vettii originally had paintings featuring gilded cupids (like those in the red panels) on all the walls. The black frieze that encircled the room featured gilded cupids selling perfumes and flowers, making wine, working with gold, etc. On the side walls, you can see where some of the plaster has fallen away. The walls were covered with thick layers of plaster to make them smooth and suitable for painted artwork.

Here is the courtyard of the House of Vettii.

Back on the streets of Pompeii we saw this partial kitchen, perhaps in a communal cooking area or in a restaurant. The circular object in the foreground of the picture is a grindstone for making flour. Long rods could be inserted through the holes in the curved upper stone and were used to first, lift the stone (slaves or animals would do this) while grain was placed on the flat surface of the center cylindrical stone. Then the upper stone was dropped and the rods were used to turn it, grinding the grain into flour. The flour would be pushed out from the top of the middle stone, landing on the flat bottom stone where it was collected to bake bread in the brick oven in the background. That oven would probably have made good wood-fired pizza if pizza had been invented in the first century.

The gladiators’ quarters are on the right side of this picture. The training ground where they practiced was to the left of the colonnade. It was very expensive to train gladiators, making them valuable commodities, so the owners weren’t eager to have them die in battle. According to the Pompeii legend, spectators only voted thumbs up or down instead of killing the loser. At least, that’s what our guide said, but I looked it up and every website said that a thumbs up meant “live” and a thumbs down or a closed fist meant “die.” Maybe in Pompeii, that practice was only a figure of thumb.

The Forum was the center of religious, political, and cultural life. It was an open, central space with some of the most beautiful buildings in the city surrounding it. It served as the hub of the city and as the commercial center of justice, trade, markets, and worship.

The basilica of Pompeii stood here. It was primarily used for governmental, legal, and administrative purposes and for large group gatherings.

The Temple of Apollo was a place of worship in Pompeii where athletic victories were celebrated with ceremonies to praise Apollo for the victory. Gladiatorial games, theatrical performances, and festivities were also held here. A replica statue of Apollo can be seen in the photo and, on the opposite side of the field, there was a statue of Diana, Apollo’s twin sister. The original statues of Apollo and Diana are now in the Naples Archeological Museum.

According to the people in Naples, pizza was probably invented here in the 16th or 17th century among the Romans in this area. Because people at that time didn’t always have flatware and dishes, they ate a variety of foods on a piece of bread, leading to the logical development of pizza. Someone (vague, here) squashed tomatoes and made a sauce for the bread, but people were afraid to eat it because tomatoes are a relative of nightshade, a very poisonous and deadly plant. Someone (vague, again) finally convinced the people that tomato sauce was safe to eat, pizza became a big hit, and it’s now a world-wide favorite. It’s the one thing Ted and I have seen in every country we’ve visited and it’s always spelled p-i-z-z-a, no matter what the native language is.

When Ted and I went to Rome in 2019, we made a point of having gelato, spaghetti, and pizza because we were in Italy, the country that created gelato, spaghetti, and pizza. The gelato was great, the spaghetti was so-so, and the pizza was no better than ok. We mentioned the disappointing pizza to a Neopolitan waitress we met in Switzerland, and she firmly informed us that Roman pizza is terrible and that if we want good pizza, we have to go to Naples. Well, Pompeii is part of the metropolis of Naples and our group had lunch today at a pizzeria in Naples.

We could watch the crew make the pizzas and put them in the ovens. Each member of our group was served a 10-inch pepperoni pizza and our choice of beverage—water, soda, wine, or beer. Afterward, each table was served a single dessert pizza with only one piece of that for each of us. I wish I’d taken pictures of the pizzas. All I remember is that both were so-o-o-o good and the dessert pizza had chocolate on it. The woman in Switzerland was right: you have to go to Naples for good pizza.