Today, Ted and I visited the ruins of Troy which date back as far as the Bronze Age. The excavated ruins have been kept “purposefully minimalistic,” which made it hard for Ted and me to picture an actual city existing here. Frankly, we found it kind of boring, but it was nice to spend time outside in weather cooler than 100 degrees. Here’s a summary of what we saw on today’s excursion.

Troy is believed to be the site of the war described in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. The ancient city was strategically located at the southern entrance to the Dardanelles, a narrow strait linking the Black Sea with the Aegean Sea (map). There was also a land route from Troy northward to the European shore over the narrowest point of the Dardanelles. As a result of its location, Troy became an important and powerful trading center between the east and west and, during the Bronze Age, between the north and south.

The water and wind conditions also worked in Troy’s economic favor. The winds through the entrance to the Dardanelles are strong and so is the surface current that flows through the Dardanelles. Flat-bottomed, square-rigged ships had to wait for favorable southerly winds to blow through the strait—conditions that occur for only a brief time in the summer. While the ships were moored at Troy waiting for a southerly wind, the Trojans charged tolls for mooring as well as for passage through the strait.

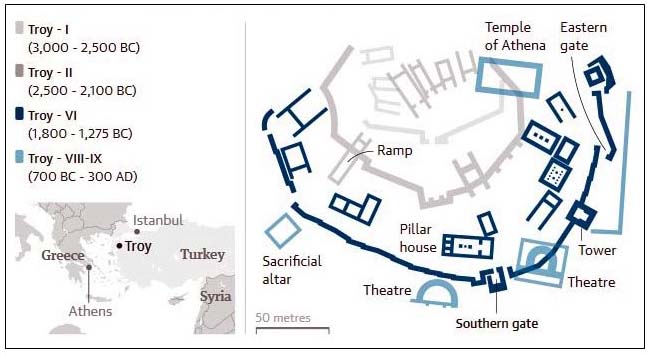

Twentieth century excavations show that as many as nine cities were built on the site of Troy. Here’s a map of how archeologists believe the cities were laid out over the years from 3000 BC to 300 AD. I think the ruins we saw were the most recent in layers VIII and IX. (That’s 8 and 9 in Arabic numerals.)

Over time, the Dardenelle Strait narrowed, due to the silt left behind after frequent floods. If you look closely (or zoom your screen) you can see a very narrow blue line–the strait–at the horizon in the photo below. I took this picture from the ancient seaport location of Troy which is now approximately five miles inland.

The photo below shows the ruins of one of Troy’s theaters. In contrast, you can see the rooftop of the modern-day visitor’s center in the upper left.

This area of Troy is believed to have been a site for offering sacrifices to the ancient gods.

Thanks to the “purposefully minimalistic” excavation and my lack of archeological knowledge, I have no idea what is shown here, so call it what you will. I call it “ruins.”

The photo below shows part of what is known as Schliemann’s Great Trench. There are markers on three of the “steps” indicating levels II, III, and IV of the rebuilding of Troy. (That’s 2, 3, and 4 for those who are Roman numeral challenged.) The Great Trench is 56 feet deep and 230 feet wide. Schliemann, one of the first archeologists to excavate Troy, began his work by digging this trench. In the process, he destroyed everything in the trench; as a result, it serves as an example of how not to excavate a site. Because it illustrates such a big mistake, it has become a notable point of interest. Go figure!

Here’s another view of Schliemann’s Great Trench in the opposite direction, facing the Dardanelle Strait.

Çanakkale, the city nearest to Troy, is a modern contrast to the ancient ruins. (Note: As a non-archeologist, I have no trouble picturing this as a city.)

Çanakkale’s waterfront is a pleasant place to walk, with lots of boats, refreshment stands, etc.

The waterfront also features—what else?! –a Trojan horse.