Murano, a small island just north of Venice, has been the home of Venetian glassmaking since the 13th century. It took 50 years to become a master glass blower, and masters usually began learning the trade in their early teens by working with their fathers and grandfathers. Glassmakers were so well respected in the 13th and 14th centuries that they had heightened social status. As of 1376, the law affirmed that if a glassmaker’s daughter married a nobleman, there was no forfeiture of social class, so their children were nobles.

In 1291, a law confined most of Venice’s glassmaking to Murano to remove the threat of a disastrous fire in Venice. Conveniently, this isolation had other benefits as well. First, it prevented the spread of Venetian glassmaking expertise to potential competitors, because either leaving the island without government permission or revealing trade secrets was a crime punishable by death. Second, the confinement simplified government monitoring of glass industry imports and exports.

Venetian glass is made with a soda-lime “metal” in an extremely complicated process that produces a shiny, rock-hard vitreous substance. The glass is typically elaborately decorated with glass-forming techniques, gilding (lots of 24-karat gold), enamel, or engraving. It’s breakable, but it’s more resistant to breakage than lead-based glass. The manager at the glass-blowing shop we visited held a beautiful Venetian glass goblet about 18 inches above a Venetian glass mirror and dropped it. It landed with a crash and a gasp from our group of observers, but neither the goblet nor the mirror cracked or broke. At the sound of the group gasp, the manager (the guy holding the microphone in the photos below) grinned and said, “I just love to scare people that way.”

The single stemmed glass that the manager dropped (or others like it) could be purchased for $155. A small jewelry pendant made of Venetian glass might cost around $30; a large vase can cost thousands of dollars. The high cost of Venetian glass is mostly due to the labor involved in making this complicated, heavily decorated glass; the price of the materials is a distant second. Ted and I looked at a glass sculpture that was about 15-18 inches high. We thought it would look nice on our dining room table, but $6,000 was too much to pay for it, even with free shipping. We were not allowed to take pictures of anything on display in the shop, but you can search “Murano glass images” to see what this kind of glass looks like.

One of the shop’s master glassmakers provided a demonstration of glassblowing. I’ve seen glassblowing demos before, but never by a glassmaker who worked this quickly. He made a vase in roughly two minutes.

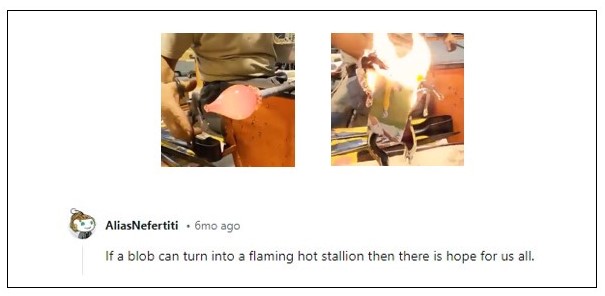

After the vase, the glassmaker shaped a prancing horse, a.k.a., a Ferrari horse, inspired by the original drawings of Leonardo di Vinci. Again, it took him about 2 minutes. He had a blob of hot glass, quickly tugged on it and bent it with his pliers, made a few quick snips, quickly pulled and sculpted it with another tool, then set it down to show us a glass horse with a flowing mane and tail.

To demonstrate how hot the glass was after the horse was formed, the glassmaker dropped a piece of cloth on it. The cloth immediately burst into flames and became ashes. The moral of the story: Don’t touch hot glass! FYI, a larger Ferrari Murano glass horse costs $6,950. A small one like the one in my photo, sells for $3,995. You can buy them online.

I found an internet video showing a Murano glassmaker forming a prancing horse, followed by an interesting comment.