Today started very early for some of the people on our Nile River cruise. I’m not sure how far away the hot air balloon ride was, but the bus leaving for the balloon site departed from our dock at 3:30 a.m. The balloon ride excursion was weather-dependent, and the go-no-go decision wouldn’t be made until the departure time. Luckily, the weather was good, so our friends didn’t get up early for nothing. Ted and I have already experienced (1) a hot air balloon ride; (2) the Great Forest Park Balloon Race; and (3) the Albuquerque Balloon Festival, so we slept in until 6:30. When we got up, we saw hot air balloons across the Nile from us. Maybe some of our group members were in them. We couldn’t ride in them like the early birds did, but we could enjoy how beautiful and peaceful they looked.

Today was another major highlight of our visit to Egypt. We visited the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens near Luxor. On our way, we passed the excavation sites pictured below, as well as many others. As Hanan said, “There is something under everything in Egypt.” As a result, excavations usually yield results. In fact, the Egyptian government is moving people out of the Valley of the Kings to allow for more excavation. The picture below shows part of the excavation of the Lost Golden City at Aten.

I don’t know what’s being re-discovered in this photo, but that’s pretty much what the landscape looked like all the way along our route in the Sahara Desert.

When we were at the Step Pyramid and I learned that we were going to go into the tomb, my first thought was “Great! It will be cooler down there.” That was so-o-o-o not true! I was hoping for cave-like temperatures of 55 degrees (I would have settled for 85 degrees), but that was not to be. The reasons: (1) There’s a lot of heat in the air; (2) there is probably at least as much heat in the sand and the rocks that hold the desert heat; (3) the tombs have little air circulation inside; and (4) the tombs have been storing heat over the centuries just like the sand and the rocks. The result: It’s even hotter underground. Amazingly, it was a relief to come out of the tombs into the 110-degree heat!

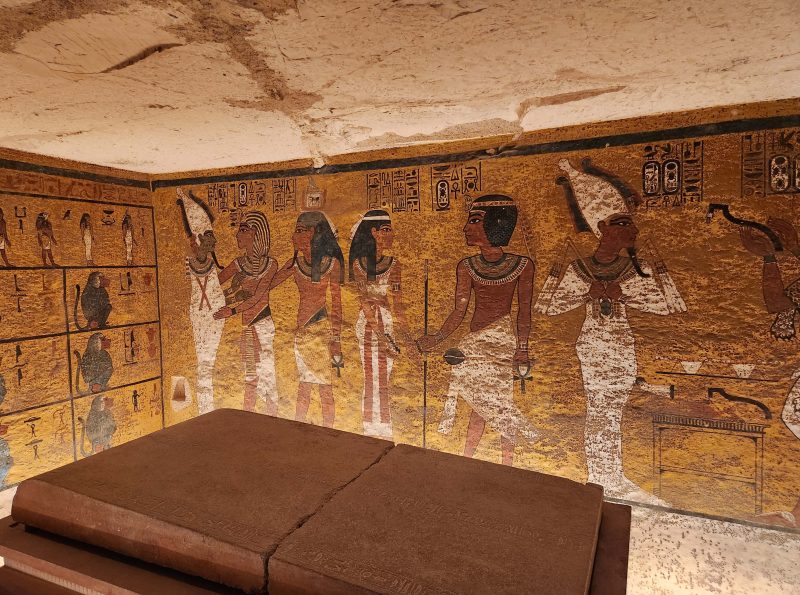

The kings chose this area for their tombs because it was hidden and would therefore prevent robbers from finding the treasures in the tombs. By this time, the pharaohs had given up on labor-intensive pyramids. In addition, pyramids were essentially a beacon to grave-robbers, clearly announcing “Come in, come in. There’s a lot of good stuff in here for you to steal!” There are more than 60 pyramid-less tombs carved into the rocky hills in the Valley of the Kings. Our first stop was King Tutankhamun’s tomb (photo below). The pyramid-shaped pile of sand and rock over the entrance was added after the excavation of the tomb.

Typically, kings added to their tombs over the years of their reigns. King Tut died when he was 19, having ruled for only nine years, so his tomb is small. The photo below shows King Tut’s sarcophagus. The tomb was discovered in 1922 and, after scientifically examining the mummy, the mummy was replaced in 1926 and is still inside the sarcophagus.

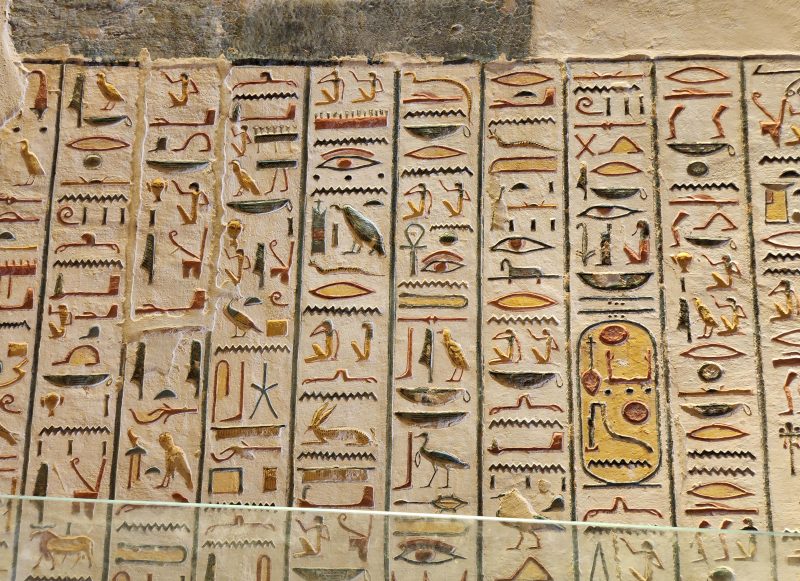

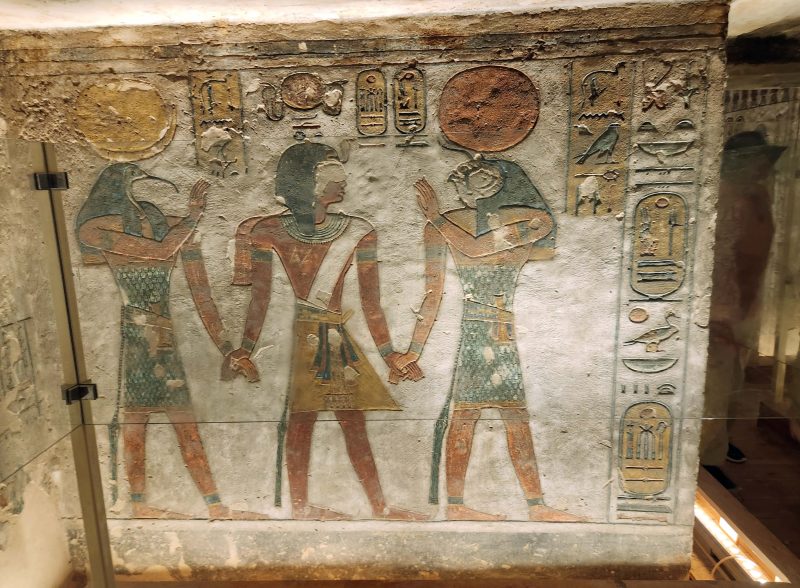

Three coffins were discovered inside King Tut’s sarcophagus. The outer two were made of wood, covered in gold and semiprecious stones. The third (inner) coffin held the king’s mummified body and was made of solid gold. The image of a pharaoh is that of a god, and the gods were thought to have skin of gold, bones of silver, and hair of lapis lazuli, so the death mask of Tut that we are familiar with shows him in his divine form in the afterlife. It is regarded as one of the masterpieces of Egyptian art. (It was one of the things we could not take pictures of in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.) Below are pictures of some of the hieroglyphs inside King Tut’s tomb. King Tut’s tomb is less splendid than many of the other tombs. Its main claim to fame is that it is the only tomb archeologists found intact, with a literal treasure trove of artifacts inside, as well as the undisturbed mummy.

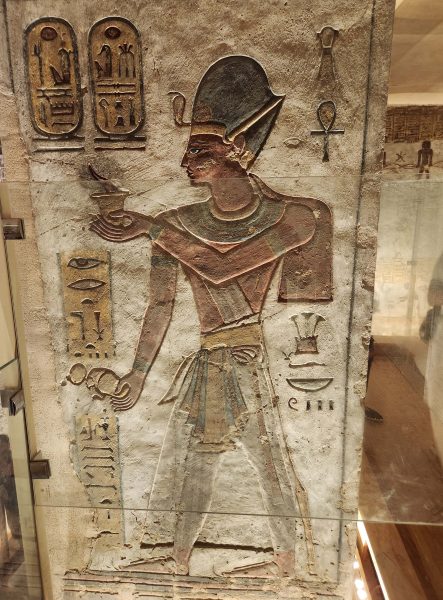

The next tomb we visited was that of Ramses II. He lived to be around 90 years old and reigned as pharaoh for 66 years, so it’s not surprising that his is one of the largest tombs (26 rooms) in the Valley of the Kings. All of those rooms were cut into the subterranean rock!

Ramses II was one of the greatest pharaohs of Egypt and ruled during Egypt’s Golden Age. He is known for his military and cultural accomplishments, his good leadership, and the monuments and temples he built, including the Karnak Temple. On a personal note, he had over 200 wives and over 100 children. It makes you wonder when he had time to do any of those other things he is remembered for.

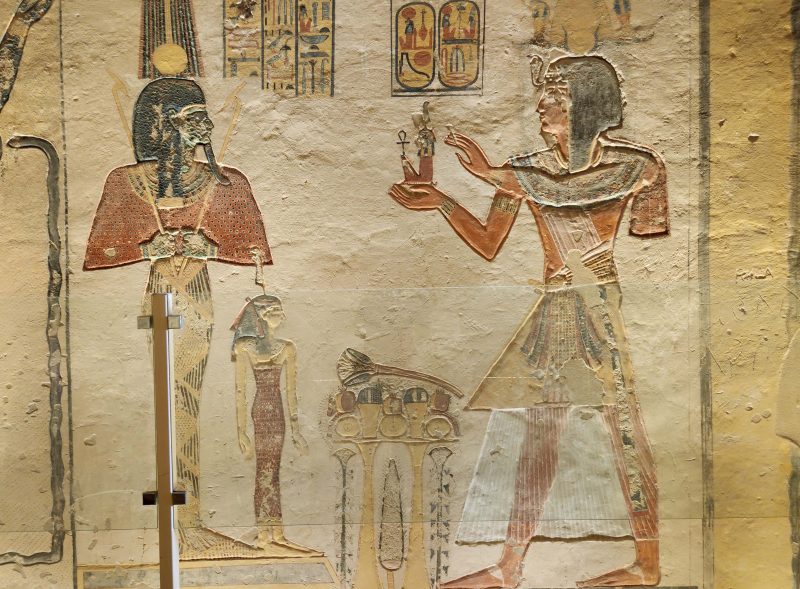

In the photo below, you can see a hallway in Ramses II’s tomb. The tomb is so large, there are other hallways branching off from this one.

Here are close-ups of some of the beautifully detailed hieroglyphics in Ramses II’s tomb.

We left the Valley of the Kings and moved on to the Valley of the Queens, where over 90 tombs have been discovered so far. The queens had to be buried separately from the kings, so the Valley of the Queens is on the opposite side of the mountain from the Valley of the Kings. It was originally intended to serve as the burial grounds for the royal queens of ancient Egypt, but princes, princesses, and other high-ranking nobility are also buried in the Valley of the Queens. Question: Does anyone besides me think it’s odd that the men liked women enough to have 200+ wives and to father 100+ children, but could not tolerate women enough to be buried beside them after they were dead?

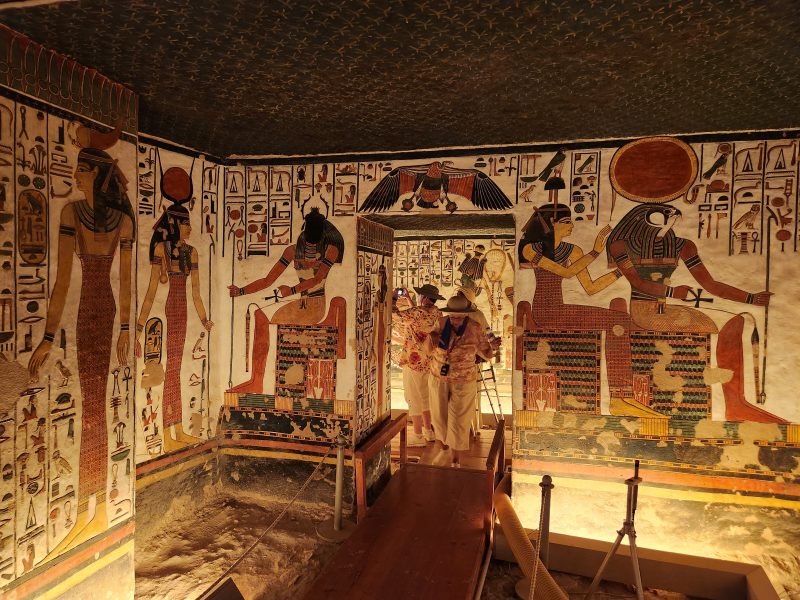

The most beautiful and best-preserved of all the tombs in the Valley of the Queens is that of Nefertari, the first of the Great Royal Wives of Ramses II. Nefertari always wanted to be a man and wore men’s clothing; as a queen, she wore a king’s crown. There were other queens in Egypt, but Nefertari was the only female pharaoh, and she very successfully ruled Egypt for 20 years.

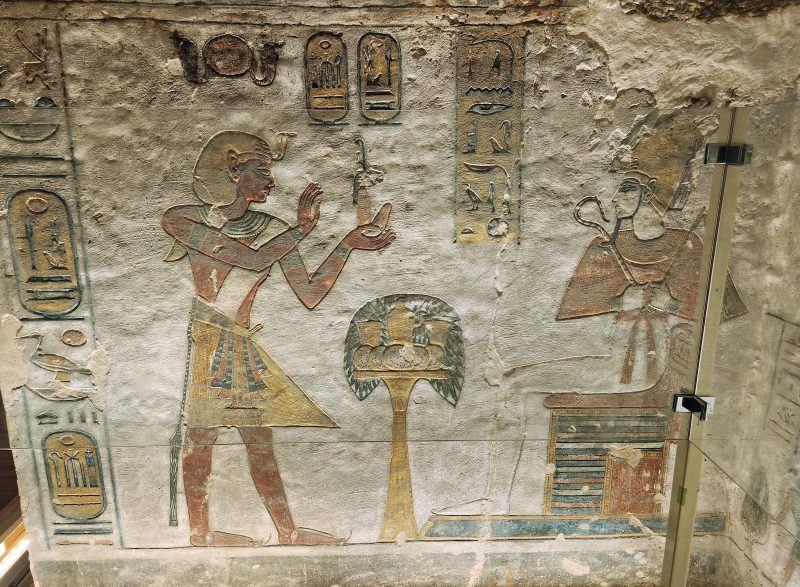

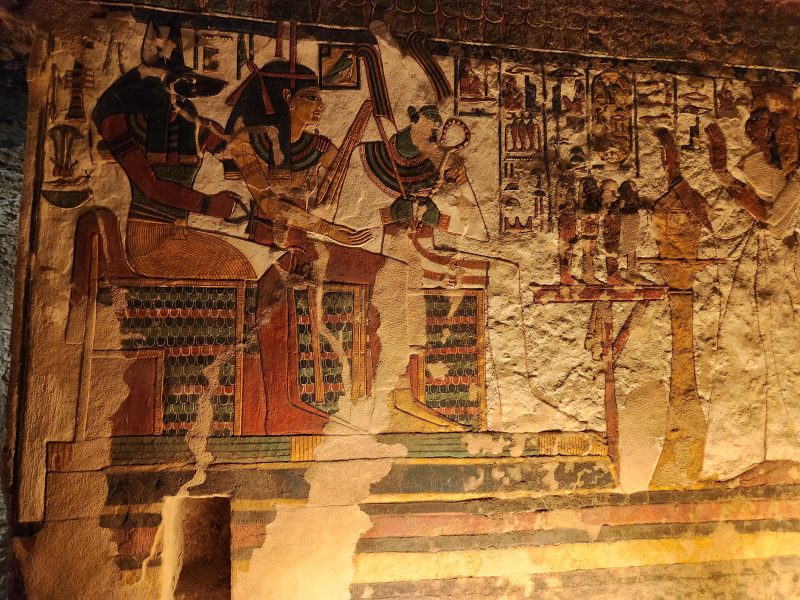

Nefertari’s tomb has been described as the “Sistine Chapel of Ancient Egypt.” All the hieroglyphs we’ve seen in the tombs we’ve visited are in their original state. The dry climate of Egypt and the fact that the tombs are underground provide ideal conditions for preserving artifacts like these. Some of my photos of Nefertari’s tomb are below. It is, beyond a doubt, an extremely beautiful place to visit—more like an art museum than a tomb.

After spending most of the day admiring hieroglyphs underground, we came up for (hot) air and visited the Colossi of Memnon, two massive stone statues of Pharaoh Amenhotep III that have stood in front of the Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III to guard it since 1350 BCE. The temple was originally the largest and most opulent in Ancient Egypt (larger than Karnak), but very little of it is left today, except for the Colossi. Now, I guess they guard the temple ruins.

Our last stop of the day was at the house of British archeologist and Egyptologist, Howard Carter, the man who led the team that discovered the tomb of King Tut. The house was not remarkable, so I didn’t take any pictures of it. The best thing about the Carter House was that it was surprisingly cool inside (relatively speaking), with spacious rooms and a lovely breeze—yes, a real breeze! —on the front porch.

And that concluded our time in the Valleys of the Kings and the Queens. I mentioned in an earlier post that much of the stone for the Great Pyramids was quarried near Luxor and shipped to Giza. Obviously, the desert is filled with sandstone and granite, but this area also has a great deal of alabaster, and alabaster factories are plentiful. One of them is shown in my picture below.